My PhD project combines participatory visual methods with ethnography and archival research to understand the meaning of the border for its inhabitants. As a sub-study of the Reel Borders ERC project, I hosted Participatory Filmmaking (PF) workshops to study ‘border narratives’ in three distinct borderlands: Derry, at the Irish border; Ceuta, the Moroccan-Spanish border; and Adana, a Turkish city that has become home to over a quarter of a million Syrian displaced people.

PF involves collaborating with a community to create films. This process draws from various practices such as storytelling, performance, archival collection, autoethnography, interviews, voiceover, video recording, and viewing. In border and migration research, PF has been used to create counter-narratives that provide a first-hand understanding of displacement, placemaking, and belonging. It has the potential to make bordering and migratory experiences more tangible. However, it's crucial to acknowledge and consider power dynamics that may arise during PF projects, especially in borderlands, where cultural, gender, class, agency, and political inequalities are exposed. In this entry, I will share what I learned from my PF practice on how to engage the participants as well as some reflections on power dynamics.

In the field: co-creating films in the borders of Ireland, Turkey-Syria, and Spain-Morocco

In April 2022, we started a three-month PF workshop in Derry. We recruited nine participants from both sides of the Irish border to create four documentaries portraying their visions on the border. Later, in October 2022, we conducted a three-month workshop in Ceuta with 13 Moroccan women living and working in the city undeclared. They created 26 short web documentaries highlighting their forced immobility after the COVID-19 border reinforcement. Finally, we concluded our fieldwork in December 2023 with a third workshop in Adana, where 25 participants addressed the intricacies of the city's conviviality between Turkish and Syrian communities for one month.

Throughout my journey of working with different border contexts and human experiences, I became aware of the need to modify my workshop designs to meet the unique needs of each group. Two fundamental principles guided me: reflexivity and reciprocity. Reflexivity involves questioning our methods systematically (Hibbert et al. 2010: 48), whereas reciprocity involves mutual negotiation of power and meaning through give-and-take (Lather, 1986: 263, mentioned in Roberson 2000: 311). In other words, I considered participants experts and not mere 'data providers' and critically examined my research design to tailor it to their goals.

The importance of understanding participants’ objectives

One of the most effective ways to keep participants engaged during and especially after the fieldwork is to understand their motive for participation. For example, Irish participants wanted to improve their filmmaking skills and showcase their films at film festivals. Participants in Ceuta aimed to share their experiences with policymakers and citizens rather than becoming filmmakers themselves. In Turkey, students wanted to use filmmaking to connect with Syrian colleagues and neighbours. In this way, discerning the unique objectives of each participant group helped me adjust the method according to the spaces and geographies of the border.

Four participants of the PF workshop in Derry, Emer O'Shea, Seamus Gordon, Michael McMonagle, and Tom Hannigan, were part of a Q&A session moderated by Sunniva O'Flynn, Head of Irish Film Programming, at the Irish Film Institute in Dublin © The author, September 2023.

Remaining methodologically flexible

Another strategy is to tailor interviewing methods to better suit the individual background of the participants. For example, I employed different interviewing techniques depending on geographical context and citizenship status. In Ireland, walking interviews along old checkpoints and today’s blurred territorial borders helped discuss cross-border and cross-community experiences. In contrast, in Ceuta, participants could not cross to Morocco due to the border reinforcement after COVID-19, which forced us to remain on the Spanish side. Moreover, they requested that I work for them as a filmmaker to help develop and share their stories of immobility and long-term precarity with politicians. The reason was simply that these women attended the workshop after working 8 hours cleaning and caring for others, which is physically demanding. Hence, although we had a few filmmaking sessions, we relied on visual archives created before the workshop.

During the sessions, the participants wanted to share their stories over a cup of tea in a way that felt safe and would not negatively impact their chances of regularisation. Indeed, most of them wanted to remain anonymous. We used non-visual methods such as oral storytelling and reflexive voiceover recording to ensure this. Moreover, we created films with blurred faces and faceless films to safeguard their identities. As I wrote during my fieldwork after one of the first sessions:

“Can film be a useful tool to make their stories visible while keeping their identities anonymous? How can our cinematic collaboration respond to the situation they are experiencing without re-victimization? And what is my position as a Spanish woman born and raised in Ceuta, coming from a coloniser country that historically subjugated our neighbour, Morocco?”

Involve everyone in the dissemination process

When working with individuals excluded from citizenship, it is crucial to be aware of their vulnerabilities in terms of (im)mobility and exposure. This requires critical reflection on how to achieve genuine participation at all stages, especially when it comes to sharing their films. In Ceuta, we came up with a solution to create individual web documentaries, which we collected in ABCeuta: the Alphabet of the Border. This approach made their films available online since the participants could not physically travel to discuss and present them. The webdoc responds to their demand to increase their visibility to local, national, and European politicians and also includes a petition for their regularisation.

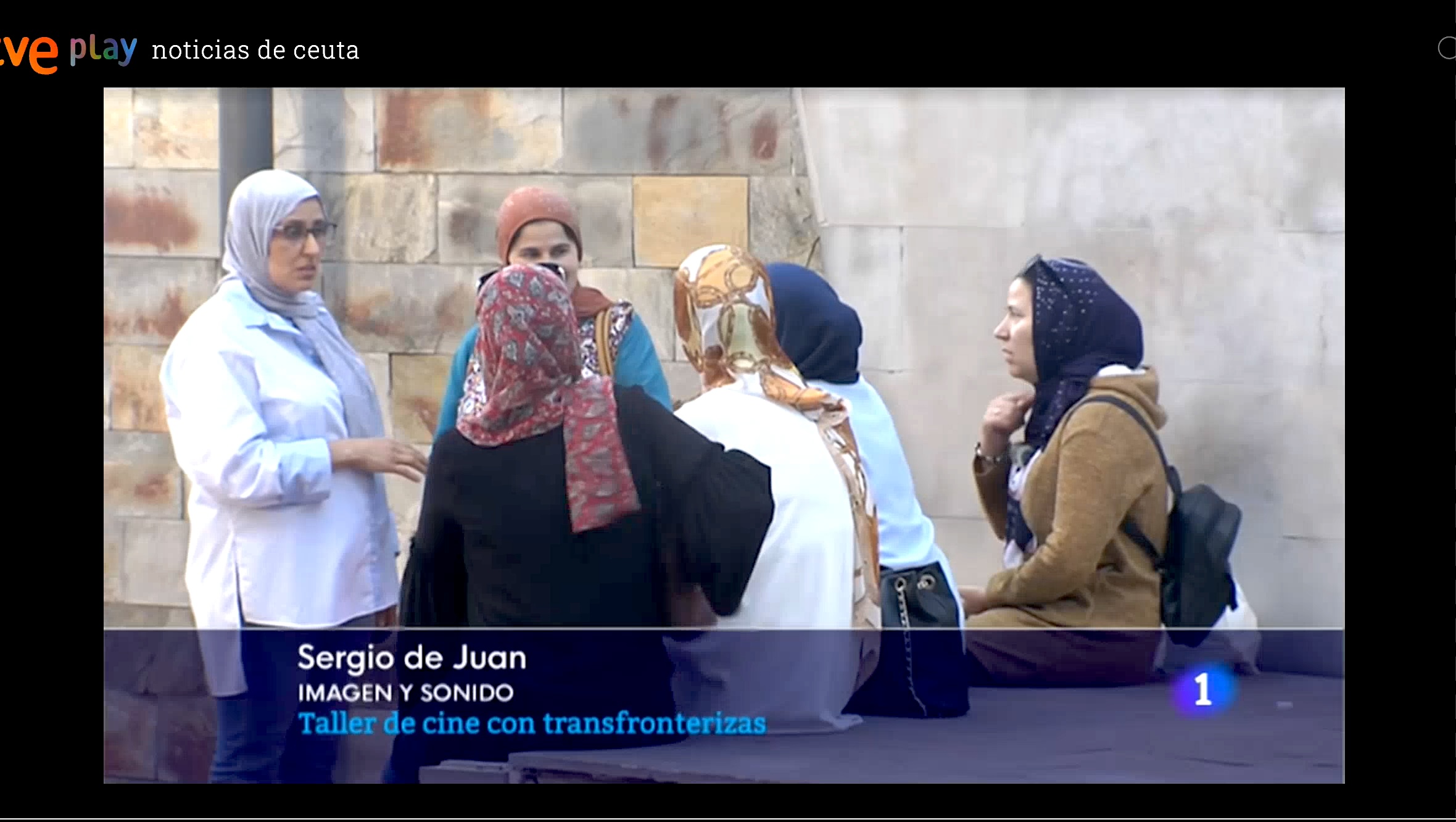

Six participants of the PF workshop in Ceuta, Faty, Fatima, Nora, Hafida, Laila, and Selma, were featured on Spanish TV news during the launch of the workshop © TVE, November 2022.

Promote dialogue and cross-cultural interactions

When a PF workshop involves different communities, the film can foster dialogue and provoke encounters that are otherwise unlikely to happen. The workshop in Adana involved students from Turkey, Algeria, and Syria. During these sessions, participants highlighted the economic and cultural challenges of integrating Syrian communities in Turkey due to everyday bordering and racism, exacerbated by language barriers separating the communities. Their experiences were captured in the two films we co-created which were subsequently screened for Syrian students from the Çukurova University Academy. They shared their reactions on Instagram:

“The creators of the films were happy to share their stories with the Syrian people to provide a nuanced portrayal of the Syrian community without resorting to generalisations. One of the films was filmed on Syrian Street (Koca Vazir), a street in Adana that is often unfairly judged. One of the student groups visited and filmed the street, and their portrayal somehow challenged preconceptions.”

The Çucurova Academy students shared their experience on Twitter after discussing the workshop pilot film in a screening at the Faculty of Communication of the Çucurova University © Reel Borders, December 2024.

After the workshop, the Turkish students began referring to themselves as "the generation of change”.

Through my fieldwork experience, I learned that Participatory Filmmaking (PF) can be a powerful tool for knowledge production and education that can positively change the communities we engage with. When combined with a reciprocal approach, the flexible nature of PF allows for deploying different methods and practices in each location to co-design unique workshops that align with participants' goals. While measuring the impact of our efforts can be challenging, we were able to meet the needs of all parties involved and work towards creating engaged science.

More info about Reel Borders: here

To read other PhD blog posts about participatory filmmaking: here and here

Funding:

This article is part of the research projects Reel Borders (European Research Council Starting Grant #948278) and Institutional Documentary and Amateur Cinema in the Colonial Era (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation funding PID2021-123567NB-I00).

References:

Hibbert, P., Coupland, C., and MacIntosh, R. (2010) ‘Reflexivity: Recursion and Relationality in Organizational Research Processes’, Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 5/1: 47–62.

Lather, P. (1986) Research as Praxis, Harvard Educational Review, 56, pp. 257–277.

Robertson, J. (2000) The three Rs of action research methodology: reciprocity, reflexivity and reflection-on-reality, Educational Action Research, 8:2, 307-326, DOI: 10.1080/09650790000200124

Bio

Award-winning documentary filmmaker and a PhD fellow at Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) and University Carlos III of Madrid (UC3M). She is part of the REEL BORDERS ERC Starting Grant project, focusing on participatory filmmaking as a tool for challenging border epistemologies from below. Her films and research address themes of im/mobility, migration, and everyday bordering. As a filmmaker, she has directed "Border Diaries" (2013), "Hotel Nueva Isla" (2014), "Connected Walls" (2015), "Exile Diaries" (2019) and "Between Dog and Wolf" (2020). Her films have been screened in film festivals and art venues such as the Berlinale, Rotterdam IFFR, MoMA Documentary Fortnight and the Lincoln Center.