In the ongoing effort to disrupt oppressive relations in academia, there is a call to centre the body as a departure point from where to situate (and unsettle) the interweaved relationship between knowledge and power. Considering the body as an epistemological and ontological base has allowed us to map the lived, embodied experiences of those who move. It has also shifted top-down perspectives on migration towards more nuanced, muti-scalar approaches that consider migrants’ narratives on identity(ies), religion, family, gender, and memory, among others. Thus, a focus on mobile/displaced bodies offers possibilities to enlarge the boundaries of migration studies, addressing complex and often invisibilized entanglements between migration and oppression while re-imagining the process of knowledge creation with migrant communities.

Since March 2020, I have been immersed in the intersections of migration and the body as part of my PhD project, which explores academia’s critical engagement with forced migrants. But it was not until I met the PE ladies, a group of eight forced migrant women from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda living in Gqeberha (formally known as Port Elizabeth), South Africa, that I set out to address a key priority for the women at the cuspid of the COVID19 pandemic: their access to sufficient and satisfying food for themselves and their loved ones.

Pulao rice with lamb. Photo taken by Anitah (pseudonym), a Ugandan forced migrant in South Africa.

Food practices in (forced) migrants’ lives

Gathering ingredients (across local markets, corner shops, communal gardens), cooking (peeling, cutting, boiling, grilling) and eating (often with friends and family) are food practices that link the body to social, cultural, and environmental contexts. In this matter, African feminists such as Desiree Lewis (2016) have noticed the way labour around food is shaped by power imbalances, historically relegated to racialized, working-class women. She calls to approach food beyond its functional properties to then appreciate the way it enables experiences of pleasure, connectivity, and contentment as (unexpected) manifestations of freedom. Migrant communities (including me as a Mexican based in the Netherlands) illustrate this as we carry culinary knowledge and ingredients that connect us with our motherlands while adapting recipes, learning new cooking techniques, exploring diverse ingredients, and cultivating transnational food links.

The PE ladies and I demonstrated our culinary expertise in Food for Change, an online project in which we shared over thirty cooking recipes that nourished our households during the pandemic. We recreated and shared traditional and new recipes through videos, voice memos, text, and photos. By combining diasporic ingredients with local ones to “eat just like home”, as one of them described it, we fostered a sense of connectivity and joy in times of isolation and rampant anti-migrant discourses. In doing so, we made the kitchen a space from where to unsettle power.

The politics of food

In Food for Change, I noticed the women’s and my own bodily capacities to cook and share food became a form of political resistance (see Ocadiz Arriaga, 2023). This was particularly true for the PE ladies, as oppressive discourses intensified during the pandemic, targeting African migrants as aliens who represent a threat in a society still grappling with colonial and apartheid structural inequalities. As migrants are constantly dehumanised and criminalised, the participants in Food for Change were able to foster a sense of community and belonging tied to their places of origin while also grounding their everyday lives in Gqeberha. They achieved this by connecting theory and practice in home-cooked meals that stimulated sensorial, emotional, and physiological enjoyment for themselves and their loved ones.

Experiences of enjoyment triggered by food also reached the online realm, as we used WhatsApp to describe bodily sensations of satisfaction, such as the bright colour of fresh vegetables or the essence of spices, to invite other participants to recreate delicious meals. The project aimed to become a process of co-creation, where the women’s enjoyment experiences were central, and their narratives could guide the research process and the possible outcomes. This way, we strive for collaborative and communal knowledge cultivation that steps away from re-traumatizing narratives of forced migrants as a threat to instead open spaces for their embodied subjectivities of pleasure in times of crisis.

Homemade recipes of belonging

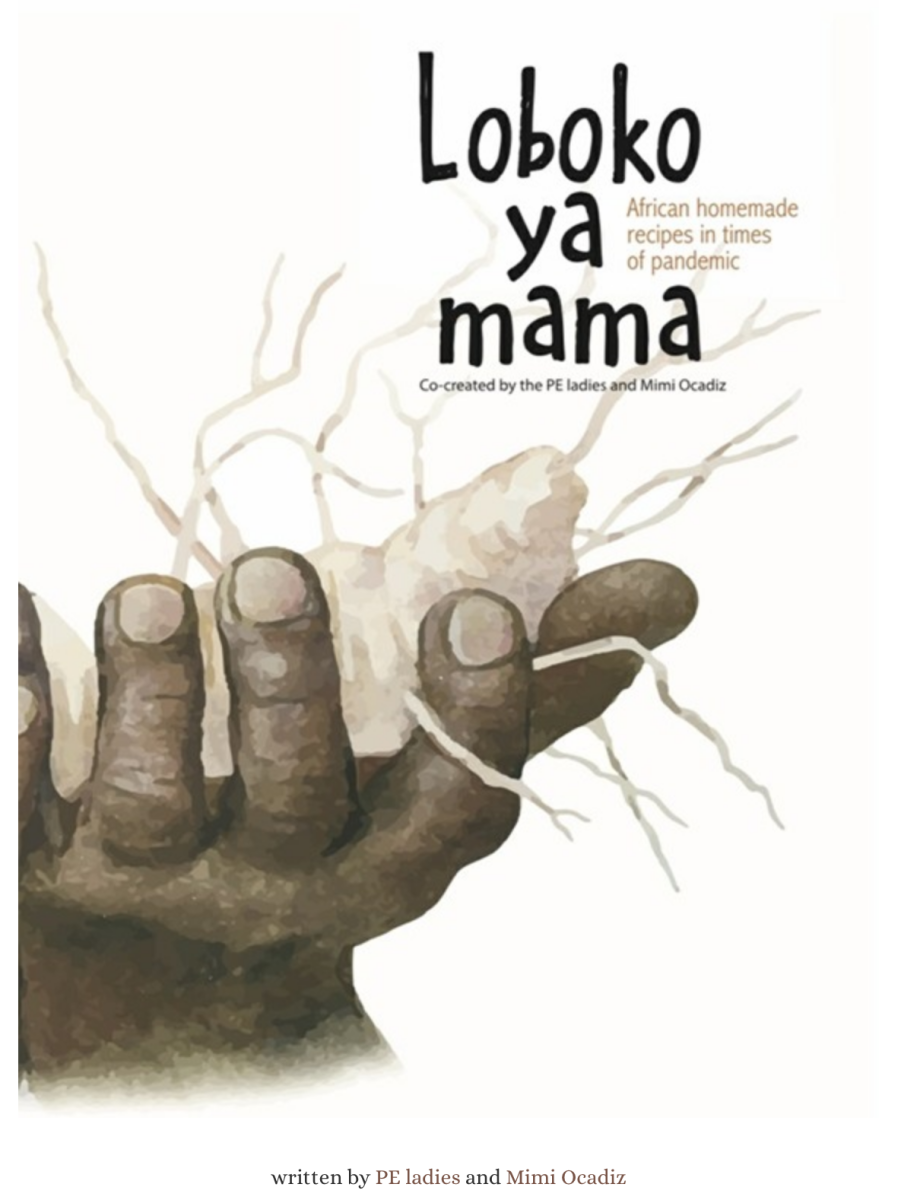

After several individual and group conversations, the PE ladies and I decided to safeguard their culinary knowledges in a recipe book. Together, we selected sixteen homemade recipes, self-written introductions and tailored portraits of each woman, to present them as rightful, resourceful and resilient agents of culinary knowledge. We intend to advocate for further critical and creative use of food practices to counteract anti-migrant discourses in South Africa and beyond. That is why we have named the book Loboko ya Mama, a phrase in Lingala which literally means ‘mothers’ hands’, referring to the women’s bodily capacities to stimulate joy, satisfaction, and a sense of belonging through mouth-watering dishes.

Loboko ya Mama: African homemade recipes in times of pandemic have been published by Cameroonian editorial Laanga.

References

Lewis, D. (2016). Bodies, matter and feminist freedoms: Revisiting the politics of food. Agenda, 30(4), 6–16.

Ocadiz Arriaga, M. A. (2023). ‘Loboko Ya Mama’: Homemade recipes of belonging. Agenda, 37(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2023.2179410

Bio

Miriam is a multidisciplinary researcher and creative writer focused on migration and mobility from an (African) decolonial perspective. She holds a Research Master's in African Studies and recently completed her PhD at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam within the Refugee Academy project Engaged Scholarship: Narratives of Change. Miriam is currently involved in the documentary project Queer and Trans Exiles: Dis/connection of Home, where she collaborates with LGBTQI+ communities in Brazil and Mozambique. Miriam is also searching to embark on new opportunities to continue supporting social justice, this time focusing on the intersection of migration, gender and climate change.